Borderlands and Central Park

19th Century engravings, countryside, truth, The Dakota, and Central Park. Scattered thoughts.

Central Park rewards scrutiny, especially the views espied from within the park itself. I made some observations on a walk through the lower half today and want to share them with you all.

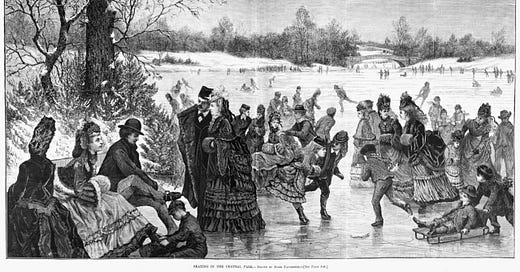

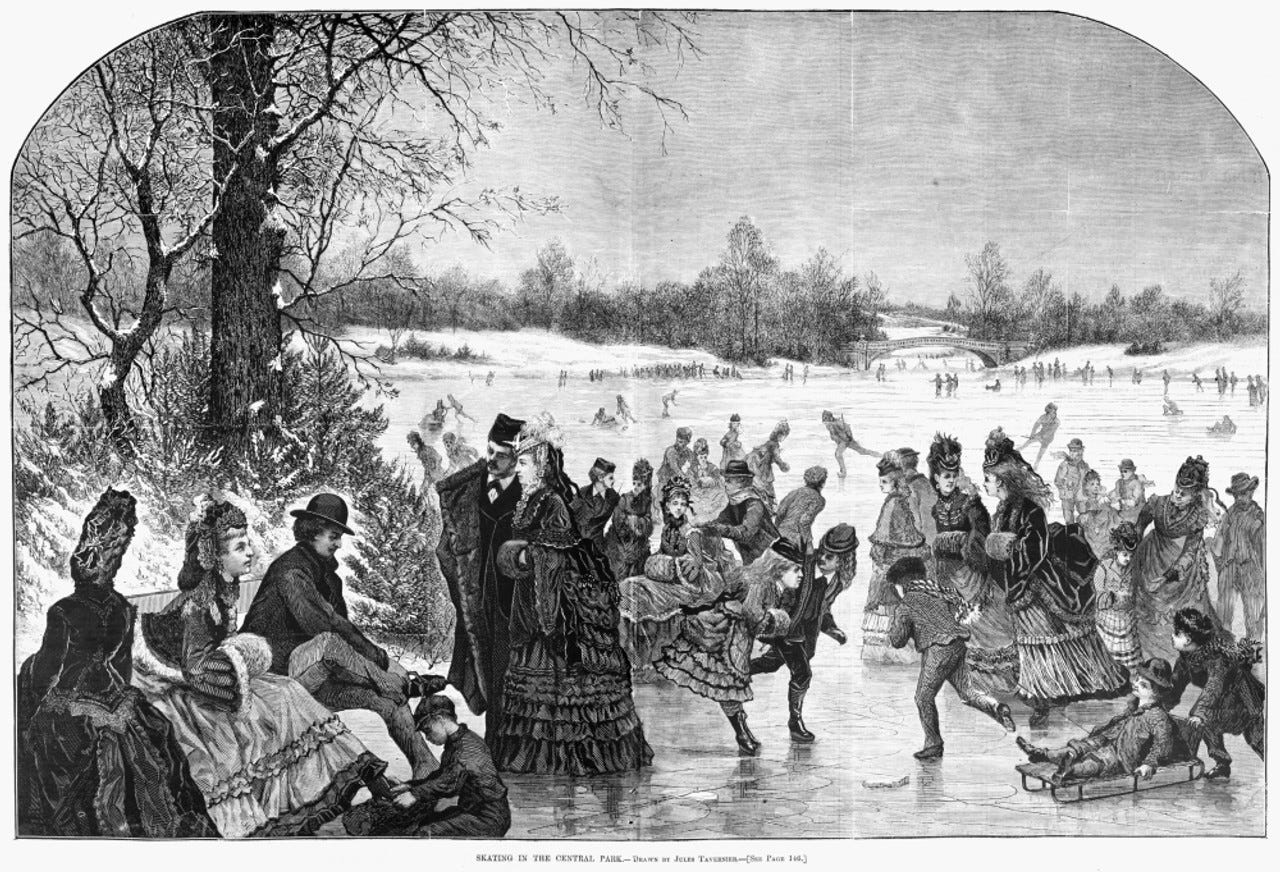

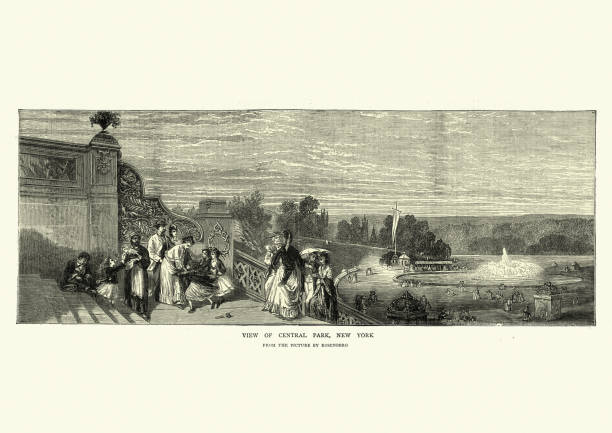

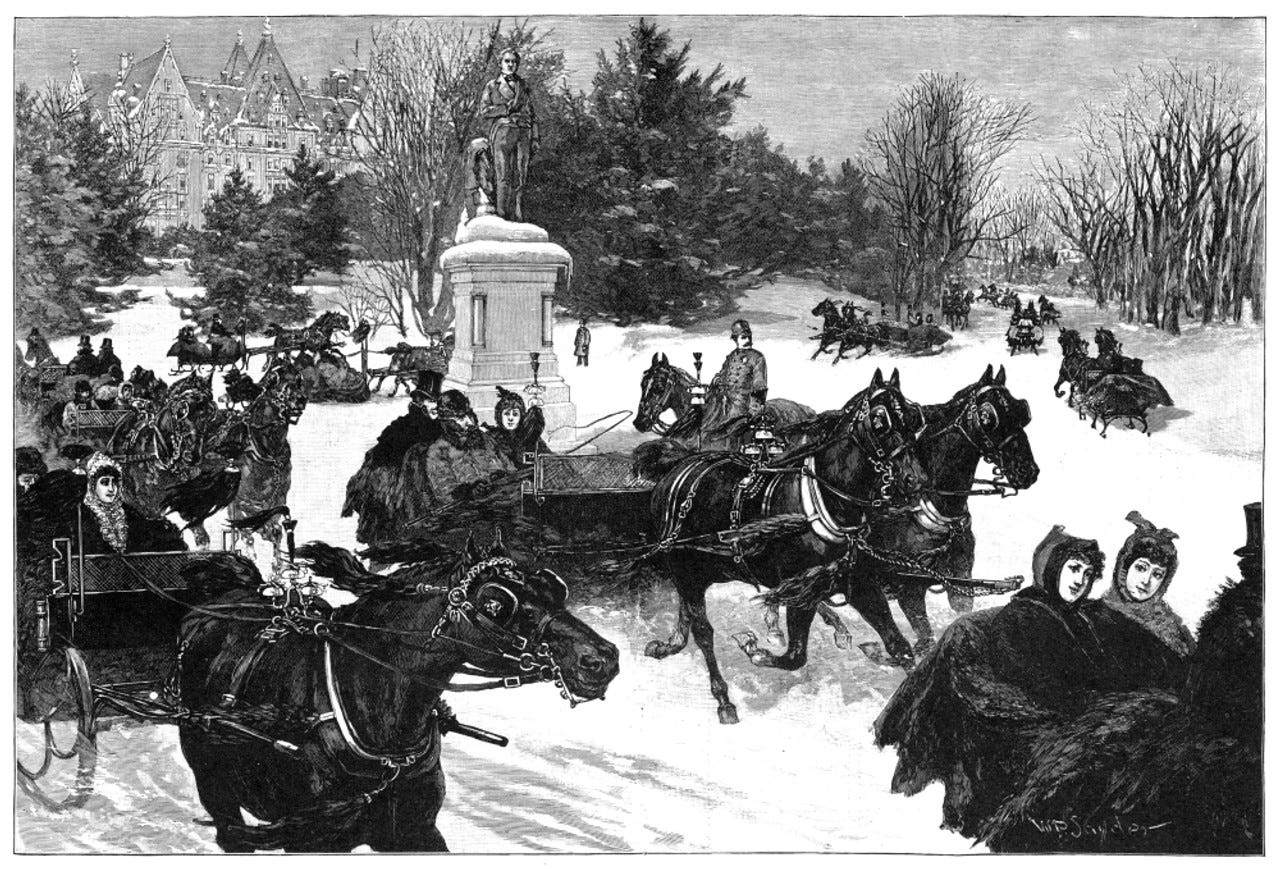

Equally akin to Disney Land and botanical gardens, Central Park presents a fantasy: 843 acres of purpose-built “countryside”—complete with rambling paths, cottages, ponds, and even a small castle—in the heart of Manhattan. It is a utopian impossibility, embellishing on European ideals of quaintness that have been with us since Roman times. This initial framing of the park is easily seen when comparing engravings from the decades surrounding Central Park’s inauguration in 1876 with European landscape paintings from the previous centuries. Here we see the park as a center for human commotion, for the joy of the masses—skaters mass and tangle like dancing peasants from the Dutch Renaissance. Here, as in many Constable paintings, the landscape itself—augmented by the human presence—is the main feature, and what houses or towns there might be are shunted to the background. (This similarity is hardly an accident. Olmsted and Vaux, the design team behind Central Park, were obsessed with the British planned parkland. A simple google of “Olmsted British Parks” will tell you plenty, plenty, plenty about that.) However fantastical the lenses of Bruegel and Constable, their images stand without pretense: Constable painted in small towns, and Bruegel’s landscapes hold no claim to pure reality. Illustrative engravings from the era before mass-photography, however, make an inherent claim to reality. They were the images of contemporary truths, the new technology of the masses. What is so striking about the Early engravings of Central Park, then, is the absence of what makes it “central” in the first place. Even in the images with clear, long vistas, one feature is missing: New York City.

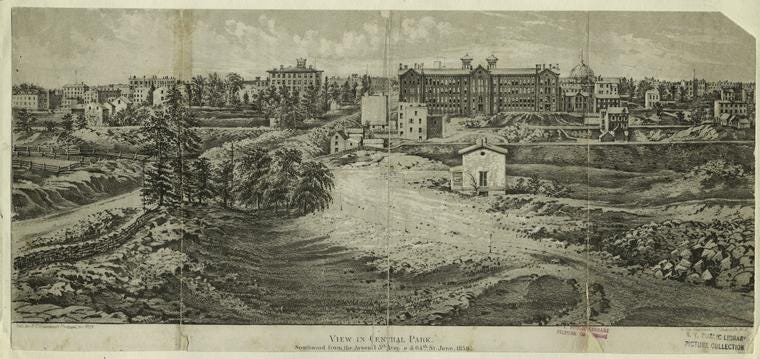

Integral to Central Park’s very nature—indeed displayed in plain view by its very name, “Central”—is its location directly in the middle of New York City. Therein lies the excitement, the uniqueness. Why, then, disregard the city in these early depictions? The first, and most readily apparent reason is that Olmsted and Vaux intentionally hid it from view and manicured the park to only allow for British-tribute-views, for example of Belvedere Castle. The second is that the city hadn’t truly reached the park. Indeed, most maps of New York in the Library of Congress only show Manhattan through about 59th Street, or the bottom of Central Park. An early wanderer of the park might have only had Constable-style-views available. This availability-of-view, however, is called into question by contemporary engravings from other rural environs of New York such as Brooklyn Heights. Here, as seen in this 1831 engraving below, the city is thrown into relief of the countryside. Perhaps there is no city in early depictions of Central Park simply because there was no true city visible from the park?

Looking at the towering fore-, main-, and mizzen-masts of schooners, the billowing factory-smoke, and the piercing steeples of downtown churches—Trinity Church’s 1846 spire rises 281 feet above Broadway and was the tallest building in the United States at the time—this doesn’t ring true. Where is the smoke certainly curling upwards from tenement fireplaces behind Central Park skaters? Where are the rooftops of the new developments springing up around the park’s borders? The contrast between views from within the park looking north versus looking south proves the selective nature of these early depictions. Popular engravers deliberately left out or selectively depicted Central Park to avoid images of the city.

In the 1880s, however, one starts to see the city creep into engravings of Central Park just as the great northward expansion on Manhattan was kickstarted by the building of The Dakota apartment building directly bordering the park between West 72nd and 73rd. Not coincidentally, it is The Dakota that we see first rising above the trees of the park two years after its completion in 1884, marking the park’s pictorial apposition with the city. I say apposition and not opposition on purpose: there is no sense of discord or conflict between the encroaching city and the park, rather they are simply placed together. If anything, The Dakota seems a beneficent presence in the background. Rather than looming above the trees, it seems to exist among them like a Victorian hotel, spreading apart branches with near-magnanimity. The Dakota, serene and watchful, stands in contrast with the “natural” park and the manic joy of the sleighers therein. One imagines mothers in the heated building looking with concern as their children race in the snow behind the snorting gallup of horse-teams. The park as chaotic; the city as stable: an interesting and notable reversal.

Why is it that the Dakota immediately appears so prominently in images of Central Park? In some ways, the building marked the crossing of an imperceptible threshold, breaking the liminal faux-countryside spell with its blunt immediacy. For the first time, one could look north from inside the park and see the city springing up ahead.

I’m gonna wrap it up here and return another week with more…

It’s a beautiful rainy day in New York: time for a nap.

-AW

didnt expect such wisdom this week 🤠